Headless brands and "the promise of ape community"

That time someone stole Seth Green's NFTs and kicked off an intellectual-property conundrum in the process

Editor’s note: Remember us? We published one edition, then disappeared for six months. We’ve been hard at working trying to buy Twitter for $43 billion, but unfortunately, some jabroni offered them $44 billion. Maybe you heard about it. So, we’re back to Plan A: publishing the only and therefore best independent newsletter about technology and you. (And us too.) Long live Big Content!—Ryan & Dave

Earlier this year, right around the time cryptocurrencies began their now-historic slides, somebody stole a bunch of non-fungible tokens “worth” millions of dollars from the actor Seth Green. Then, he tried to get them back in a very public and humiliating fashion, because he’d paid enormous sums of money for these digital assets, and “cast” them in his new TV show. All of a sudden, he didn’t own the intellectual property rights to his cartoon co-stars, see? But then he was able to buy them them back from a guy named Mr. Cheese for like $300,000, demonstrating the limi—actually, you know what? Let me back up a bit.

In this ‘sletter

❓Sorry, what happened to Seth Green?

🎲 Brand-as-meme

🐒 Bored Ape Marketing Exercise

🤦 Litigation recentralization

😮💨 Bored Vape vs. Poor’d Vape

🔚 Conclusion

❓Sorry, what happened to Seth Green?

The terminally online freaks reading this already know what I’m talking about here, and can skip ahead to the next section. But for the rest of you, let me try to explain in a bit more depth, because it actually matters for our purposes here:

An NFT is a blockchain-based digital asset that shows ownership over a unique item, a lot of which has tended to be digital art. (Perhaps you’ve heard of Beeple? No? Congrats, keep living your life.) Anyway, NFTs are often described as “digital receipts” because they prove ownership a given thing.

During the most recent crypto boom, Seth Green bought (“minted” in the jargon) a bunch of NFTs from then-popular projects you may have heard of, like Bored Ape Yacht Club and Gutter Cats.

Seth Green was then targeted by a phishing attack, which he fell for, accidentally giving over control of his digital wallet to a hacker.1 This is not uncommon. The hacker immediately sold off the NFTs in the wallet for lots of money—also not uncommon.

Seth Green wanted his NFTs back because he got fleeced like a rube for art that cost him over half a million dollars. But he needed them back because he used the intellectual property they represented—the cartoons—to create a live action/animated sitcom called White Horse Tavern. Not possessing the “digital receipts” for that I.P. raised some awkward questions about who actually owned it.

Eventually he re-purchased them from the person who bought them off the hacker.

Assuming you aren’t Seth Green—for whom this was apparently quite traumatic—this fracas was sorta strange and undeniably zany. Like, if you traveled back in time even just like even five years ago, made eye contact with a stranger, and told them “The shortest guy in Without A Paddle spent May 2022 cringeposting about how somebody took the online monkey he bought for the price of a condo,” they would be like “Without A Paddle sucked, man.” Actually they’d probably just sprint in the other direction, because in 2017 every part of that sentence would be absolute gibberish.

Seth Green’s Stolen Ape Saga™️ was just one of dozens of high-profile hacks, exploits, and embarrassing self-owns that unfolded before the heat dissipated on web3 and the current crypto winter set in. But I wanted to file something about this situation because I think it was a good showcase of the potential—and potential pitfalls—of a business/marketing concept that I’ve been curious about: headless brands. Let’s talk about that.

🎲 Brand-as-meme

Unless you are deeply unwell, this next bit is going to read like Shingy doing LinkedIn broetry on ketamine, and I’m sorry about that. But it’s important, so try to bear with me. Deep breath, here we go.

Back in 2019, a group called Other Internet published a blog post arguing that because “the rise of networked media has challenged the coherence of centrally-managed brand identities” and “blockchain-based decentralized organizations… giv[e] users financial incentive to spread brand narratives of their own,” the traditional idea of a “brand” was deficient to describe the growth of things like Bitcoin. They coined the term “headless brand” to describe this shift. From the post (emphasis mine):

A decentralized brand is a meme. It belongs to no one, and can be remixed by anyone. A decentralized brand can only be "designed" in a very limited sense. It is something different than a Coca-Cola, an Uber, or a New York Times. Decentralized brands are self-enforcing, self-incentivized, contagious narratives that emerge and evolve in ways that are unexpected and irrepressible.

This is impenetrably thinkboi blather, I know. The whole post is like that. But the easiest way to think about it is to consider memes themselves. Iconic memes like Soyjak, Pepe the Frog, or Chad (of virgin vs. Chad fame) are brands, in the sense that they’re recognizable expressions of media. But the significance of these memes, like all memes, depends heavily on the context in which they’re deployed, the person deploying them, the tone of the discourse at the moment of deployment… and on and on.

When people edit, redesign, or recontextualize a meme, they layer their own ideas, innuendoes, and references onto underlying object, refracting and subverting and amplifying its original meaning. They recreate and add to the meme’s brand as they see fit, and use it for their own purposes. It’s theirs and it isn’t, no one’s and everyone’s. Apply this thinking to the concept of branding: by issuing tokens and letting people buy into some shared intellectual property—say, Soyjak—you give them an incentive to go out and increase its value in the marketplace of ideas.2 Whether “it” is toothbrushes or SAT prep courses doesn’t really matter. What matters is that a token-holder acting in self-interest to sell Soyjak toothbrushes will benefit other token-holders’ interests, too, because what’s good for Soyjak Toothbrush Co. is good for Soyjak the headless brand (and vice-versa.) Each of these commercial projects, in turn, drafts off the attention generated by the at-large community's cultural exchange around Soyjak, be it in private Discord servers, Twitch streams, Twitter, IRL meet-ups, or something else. The community itself is a commercial project. The brand is everyone’s at once.

Keeping with the brand-as-meme framing, you start to get a sense for why this concept is appealing to some Web3 acolytes. Getting people organized around a shared identity, and giving them a reason to iterate, evangelize, and perpetuate… that’s the hard part of building a brand. The easy part is coming up with ways to monetize it through goods and services. Marketing is hard, costly, and time-consuming. “The ‘headless brand’ concept is basically an attempt at monetizing this process,” wrote Ryan Broderick, publisher of the excellent newsletter Garbage Day. And shortcutting it: if aspiring entrepreneurs can simply buy their way into a community of ready consumers, they don’t have to waste years cultivating it. Theoretically, at least.

🐒 Bored Ape Marketing Exercise

Let’s return now to the curious case of Seth Green’s NFT-based TV show, White Horse Tavern.

To point out the obvious, it looks pretty fucking bad!3 But the watchability of Green’s sitcom is not really the point; I only included the clip because it’s kind of hard for someone whose brain isn’t permanently poisoned by online to conceive of “what if sitcom but NFT” without seeing it. (Now you have, and I apologize.) The point is that Green’s show is an example of a Bored Ape owner deploying the intellectual property of their NFT in an effort to monetize—“exploit,” in the jargon—that property. In other words, White Horse Tavern—corny though it may be—can be understood as a manifestation of Bored Apes’ headless brand.

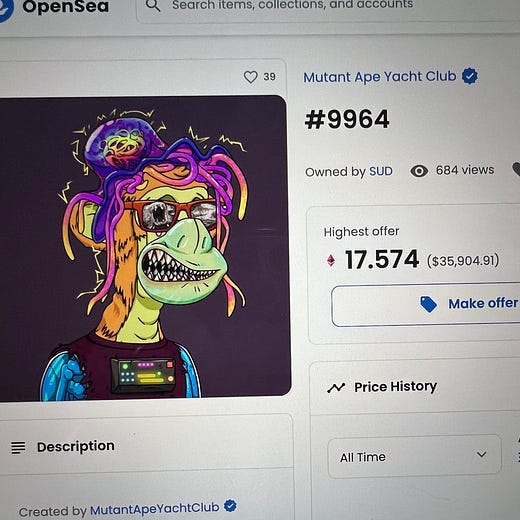

It’s not the first. Bored Ape Yacht Club (often shorthanded as BAYC) is one of the most prominent NFT projects out there, and unlike many others, it offers holders of the NFTs the ability to exploit the underlying IP for derivative commercial use, so long as those usages do not violate the project’s terms and conditions. So far people have incorporated their Bored Apes into the branding and marketing of:

And probably a bunch of other stuff, too. Remember, these businesses are all separate from one another; there’s no one like… coordinating brand standards across the various BAYC hoodies and coffees and candles for sale. The common denominator is simply that they’re all operated by someone who owns an actual Bored Ape, or by someone who has sub-licensed that imagery for commercial use. Ditto White Horse Tavern: Seth Green is exploiting his BAYC IP—an illustration of a monkey he calls “Fred Simian,” no I am not making that up—to monetize the evolving, iterative BAYC brand in the exciting world of… *rewatches trailer* ah… Who Framed Roger Rabbit rip-offs for elder millennials crippled by urban loneliness?

Which, fine, whatever, there are plenty of dumb TV shows out there. But building one around IP that’s “on-chain,” novel though it may be, carries with it the risks of being on-chain—hell, even just online. “[L]ike all blockchain concepts,” Garbage Day’s Broderick writes, the idealized vision of brand-as-meme is “wildly naive and absolutely does not line up with how the internet actually works in practice.” As poor Seth Green learned, while decentralized community brand-building is cool in theory, in practice it uh… tends not to be.

🤦 Litigation recentralization

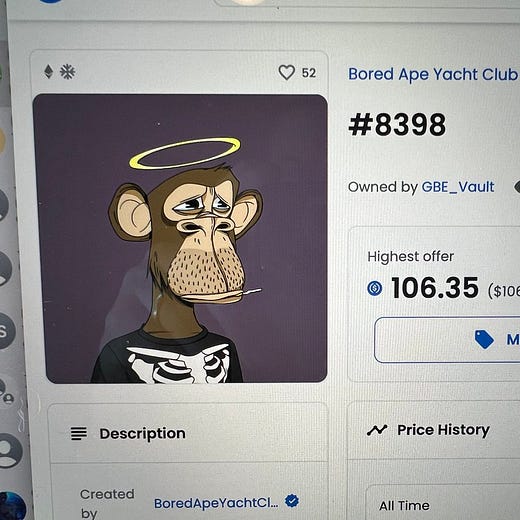

Green’s road to ruin began last summer, upon purchasing Bored Ape #8398 for around $200,000. As BuzzFeed News reported:

“I bought that ape in July 2021, and have spent the last several months developing and exploiting the IP to make it into the star of this show,” Green told [Gary] Vaynerchuk. “Then days before… he’s set to make his world debut, he’s literally kidnapped.”

The word “literally” is doing a lot of work in that sentence, given that we’re talking about a digital receipt of a digital cartoon. But maybe Seth was just exaggerating because he was upset. After all, depending on how you interpret BAYC’s terms and conditions, when his NFTs got hacked, the ownership of their IP may have transferred from Green to whoever bought them. I.e., if you lose your NFT, and your NFT is a bearer instrument, then whoever gets your NFT next is the rightful owner of its IP. Green clearly disagreed:

“Looking forward to precedent setting debates on IP ownership & exploitation,” Green wrote in a follow-up tweet addressed to Mr. Cheese, cajoling him to return the token. “We can prove the promise of ape community.” This actually happened less than six months ago. I feel like I’m going insane.

Anyway: if a court eventually decided that Green was indeed the victim of theft, and Mr. Cheese hadn’t disappeared into the digital ether (ahem), it’s possible that the actor would’ve been able to claw back his beloved Ape. Because—and this part is key—even though Web3 stuff like NFTs and crypto make bold claims about decentralization, trustlessness, and “code is law,”4 they are still subject to the same centralized, adjudicated actual laws as anyone else.5 The Verge, in a great write-up about the collision between web3 and intellectual property law, identified four potential outcomes for copyright licensing and transferring via NFTs, but as they note:

[T]here is no clear consensus as to which of these is the best solution in general. But everyone who does a project based on an NFT that does not answer these questions [about I.P. ownership] is putting an immense amount of faith in the courts to get things right if the deal goes sour and the parties end up suing each other.

Huh. Let me ask you something, dear reader: doesn’t this seem like an unnecessarily complicated and risky way to produce a bad sitcom, even when you consider the potential built-in audience it might deliver? It sure does to me! And yet, to build a truly headless brand around on-chain IP in the form of NFTs, this is a very real risk you’d have to accept, because oh my god is there a lot of theft in the NFT marketplace! So if/when your NFTs get got, your best shot at getting your NFT-based TV show back on track is to grovel publicly on Twitter, or head to court, neither of which guarantees an outcome in your favor. All of the time and effort required here could be spent simply creating original I.P. off-chain that nobody could easily steal, of course.

😮💨 Bored Vape vs. Poor’d Vape

But let’s say your IP doesn’t get ganked from your NFT wallet, and you build a successful brand of, I don’t know… premium vape cartridges around your own Bored Ape. Congratulations, you did it: Bored Vape. Except, wait a second, another BAYC holder just launched their own vape cartridge line called Cloud Apes, and they’re using their very-similar BAYC I.P. to market it. Their cartridges are inexpensive and low-quality, undercutting your market and giving Bored Vape a bad name in the process. That seems like infringement, right? But there’s nothing in the project’s T&Cs about this… so you’re headed back to court, I guess?

OK, maybe that doesn’t happen. But what if something worse happens: another BAYC holder launches, like, a payday loan company called Poor’d Ape Fast Cash. It’s huge. Because they're advertising all the time, everybody knows Poor’d Ape… and many of them assume, reasonably, that Bored Vape and Poor’d Ape are part of the same company. This sucks! You’re trying to build a premium vape cartridge brand, and this sleazy business you have nothing to do with is wrecking your brand equity. But there’s nothing in the project’s T&Cs about this… so you’re headed back to court, I guess?

OK, maybe that doesn’t happen. But what if a lot of people come to believe that the entire BAYC project is actually an enormous and esoteric reference to Nazism? Even if it isn’t, that would probably be bad for Bored Vape. (Unless your target customer is Nazis who vape, I guess?) This is no way to run a business, dammit!

🔚Conclusion

I should note that I am not an intellectual property lawyer, nor do I play one on TV. And on the web3 side, it’s true that there are more sophisticated structures for guarding against these types of pitfalls. But I think the piece of the puzzle I struggle with the most regarding headless brands is just like… why take this on? If you’re going to produce a sitcom, produce a sitcom. If you want to sell vape cartridges, sell vape cartridges.

The best brands in the world, at least as far as I, Consumer am concerned, are the ones that have a cohesive aesthetic, purpose, and strategy, controlled by a centralized owner. Memes are the exact opposite of all of that. This makes them wonderful and vibrant and alive… and ill-suited to the requirements of successful, or at least intelligible, predictable commerce. The “headless brand” concept is very sexy for obvious reasons: it’s infinitely scalable, user-generated, small-d democratic, and maybe even cost-effective. Tapping into an existing community that’s also a customer base is a marketer’s dream; creating complementary, circular, self-sustaining brand lift is the stuff viral Medium thinkpieces are made of. Most importantly, the term itself—”headless brand”—just sounds kinda futuristic, which as anyone on V.C. Twitter can confirm, is key to bamboozling people to throw money at you these days.

I don’t mean to say headless brands are straight-up hokum. It’s conceivable that they could work commercially at some point for their various participants, I think. I think? But like spinning lead into gold or chasing down the Holy Grail, it takes loads of risk and buckets of cash to even try to find out. And as Seth Green found out earlier this year, there’s no guarantee “the promise of ape community” ever gets fulfilled.

Here’s a Twitter thread breaking down the mechanics of this phishing attack, if you’re interested in that sort of thing.

Financializing ideas, turning them into assets with exchange value, is a web3 promise/pipe dream. In that fully realized future, “marketplace of ideas” is a full-on redundancy; abstract concepts could and would be bought and sold alongside goods and services.

The real-life bar it’s named for/filmed at is a legendary neighborhood joint in downtown Manhattan where literary giants like Dylan Thomas and Jack Kerouac once got blotto. I hope its owners got paid a lot of (real) money to be a part of this shit!

As crypto critic and blogger Ed Zitron wrote, the problem with relying on Web3’s code-clad security promise/premise “is obvious if you’ve met more than one person in your life - human beings are fallible and biased, and prone to making mistakes.” I.e., systems are only as secure as the people that make and use them, same as it ever was.

This of course begs the question of whether these technologies are actually decentralized at all, which is a whole can of worms that I’m not going to bother getting into here but we probably will at some point. But like, for example: when I reported on whether cocktail bartenders would be able to use NFTs to capture the derivative value of their original recipes, I spoke to several copyright lawyers were like “lolwut absolutely not what are you talking about.” (Basically.) Enforcement is critical to intellectual property defense, and enforcement still requires a centralized intermediary when you encounter bad actors (hackers, cocktail hacks, etc.) Huh!